“Goth” is a subculture and movement that has existed for over 40 years. It is a way of life that has come under heavy scrutiny since its inception, being unequally ridiculed and appreciated. The dark child of post-punk and glam rock. Its formative years were as a movement that possessed moody, dramatic and dark tones. Bauhaus and Sisters of Mercy are cited as its progenitors in the late 1970’s early 1980’s.

My love for fashion or more accurately put anti-fashion largely stemmed from my love for gothic fashion and style. Following shared values of non-conformity, individualism, darkness and creative expression it challenges the hegemonic culture society proudly romanticizes. Goth does not merely reject the conventional. It celebrates what is often misunderstood or stigmatized, embracing the beauty of darkness and the value of the outsider.

The commodification of goth aesthetics challenges its place within anti-fashion; however, its core values prevent complete assimilation, leaving goth in a perpetual state of flux between subcultural resistance and mainstream incorporation.

Core Values of the Goth Subculture

Inspired by early 1980s musical performers such as Siouxsie Sioux and Bauhaus, the goth style developed at a London nightclub called the Batcave and was characterized from the beginning by “black back-combed hair and distinctively styled heavy dark make-up, accentuating the eyes, cheekbones, and lips” (Bush 2–3). Goth evolved into a subculture as a space dedicated to the movement and its followers. This gave rise to a community raised on shared ideals of music, the macabre, morbidity, fashion and creative expression. This bond of community provides greater resistance to the assimilation of goth into the monoculture. More importantly, this bond of community is a celebration of differences and individuality.

In the same manner, the music that birthed this subculture could ultimately be its downfall. As originally underground bands became mainstream, the dilution of the artist’s message and vision became apparent. However, though the flux between subcultural resistance and mainstream incorporation is evident, the focus of goth’s music on its values of existentialism, experimentation, and rejection of commercialism prevents its complete commodification.

Goth fashion, marked by pale skin, dark makeup, and unconventional attire, stands in stark contrast to traditional Western beauty standards, subverting the idea of beauty as defined by mainstream culture (Lady of the Manners). Before goth became a subculture it was a movement, and the inherent values of this movement remain the core of every goth, finding beauty in the monstrous, grotesque in normalcy and acceptance in celebrating what society deems undesirable.

“Being goth is about individualism and encouraging diversity. When you are a freak, it is completely idiotic to uphold political beliefs that punish anyone who is not a straight, white man” (Patton, par. 5). You cannot discuss goth subculture without the politics of goths, it is the foundation of their ideology. By rejecting the hegemonic cultures the subculture promotes progressive ideologies that abandon traditions and politics that marginalize others. A fashioning of individual identity.

“The goth subculture has consistently rejected mainstream ideals, instead embracing individuality, self-expression, and a fascination with darker themes that challenge societal norms” (Newman 3). Their core values reject the mainstream values and aesthetics shared by the hegemonic culture. An acceptance of rejection would be a more concise way of framing it. Goths appreciated anything from non-traditional Western beauty standards to dressing that incorporated predominantly darker colours, which went against society’s bright and idealized style. The rejection of societal standards is another barrier the hegemonic culture faces in the erasure or assimilation attempts of the goth subculture.

While goth’s subculture remains rooted in shared ideals, its outward expression of individuality, particularly through fashion, became a key site of resistance and subversion, leading to its alignment with anti-fashion.

Goth as an Anti-Fashion Movement

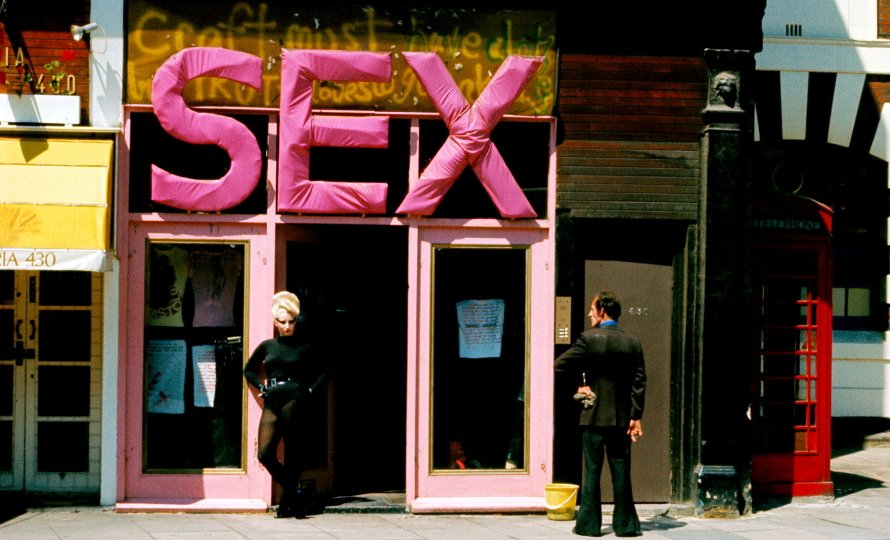

Anti-fashion came around in the 70’s initially, rejecting high fashion’s elitism and commercialism. It was a rally against the commodification of individuality. Vivienne Westwood was the initial ember that fanned the flame of anti-fashion. Her creation of the “SEX” shop alongside her partner Malcolm McLaren caused an uproar from the Chelsea elite, coupled with her provocative clothing designs that challenged conventional fashion and became synonymous with the punk ethos (Tuzio). Safety patterns, tartans and graphic tees with provocative political messages spoke to her penchant for creativity.

Similarly to the “Batcave”, her shop rallied the youth dissatisfied with societal norms and provided a sanctuary for outcasts and alternative creators. Both spaces became more than just physical locations; they were incubators for counterculture movements, embodying a shared rejection of mainstream ideals. Speaking to anti-fashion’s roots in challenging conformity and embracing self-expression as a statement of resistance. It also came along around the period goth began hitting the mainstream. The larger cultural shift that introduced anti-fashion to the world was only possible due to the goth’s values rooted in the dismissal of societal standards and embracing self-expression.

Both anti-fashion and goth are rooted in deep resistance to mainstream culture, continuously subverting expectations by prioritizing non-conformity and authenticity. As goth culture entered the mainstream, its values of darkness, individuality, and non-conformity laid the groundwork for the rise of anti-fashion, which, much like goth, sought to challenge the traditional boundaries of beauty, style, and consumerism. These are subcultures of resistance.

Similarly, both anti-fashion and goth believed in DIY, designing, sewing and repairing clothing. It tied into the core belief of individualism and rejection of mass consumption pushed by the dominant hegemonic culture. A way to build a relationship with each item of clothing you own while honing your craft. It served as both craft-based and ideological stimuli.

“Goth fashion drew heavily from history—Victorian mourning attire, medieval symbolism, and even 18th-century romanticism—all while adding elements of the macabre. This combination created a style that stood outside of time and trends, firmly rooted in anti-fashion” (Harriman 78). The goth subculture’s macabre embrace of historical and morbid elements showcases a deliberate departure from the mainstream, commercialized industry. Goth fashion is grounded in timelessness, repurposing and reinterpreting past aesthetics to create something new yet resistant to the pressures of current fashion cycles. This interplay of fabric and human, leather and lace, a romance.

Anti-fashion, as a movement, is characterized by the rejection of high fashion’s elitism and commercialism, and goth, with its individualistic, non-conformist ethos, remains a prime example of this philosophy in action.

The Commodification of Goth Aesthetics

Westwood led the charge of incorporating gothic clothing into high fashion with her “Pirate” collection for fall 1981. Here we saw the first inkling of her gothic elements on display with corsetry, darker colour palettes, and dramatic silhouettes interwoven into 18th-century pirate attire. A rebellion. However, this collection was a charade at best when analyzed from the perspective of gothic values.

Unlike a genuine attempt to promote gothic ideologies and instill a spirit of resistance in viewers, gothic elements were selected to evoke a manufactured aesthetic shock value. This is a commodification of sensationalism. Through the exaggeration and distortion of goths, entertainment was generated and profit was realized. Now whether this was intentional or not, this is the result of commodification and later hegemonic globalization.

“I am not against change, nor am I against globalization. I am, however, against ‘hegemonic’ globalization because of its consequences for homogenizing cultural diversity. I am against the asymmetrical concentration of power and wealth of ‘hegemonic’ globalization because it is driven by concentrated values and motives capable of homogenizing the world’s diverse cultural traditions for commercial and political gain” (Marsella 18). Through homogenization in globalization, cultural diversity faces extinction as all cultures are either assimilated or erased to further the dominant hegemonic culture. In the same manner, the gothic subculture faces the same dangers.

Aside from the dangers of extinction and assimilation, runway portrayals of goths promote high fashion elitism creating barriers to access. Consequently trickling down to fast fashion as the industry follows leading to greater dilution, misinterpretation and poor quality creations of gothic clothing and culture. The ultimate downside is that this diminishes the goth’s powers as a countercultural force, turning it into another fleeting trend rather than a lasting movement grounded in resistance, individuality, and anti-commercialism.

This is the main crux that challenges goth today as a leader of anti-fashion. On the other hand, with the goth’s resilient nature and values of nonconformity, its ability to remain a strong anti-fashion contender remains. Brands such as Vampire Freaks, Rick Owens, Gareth Pugh and Lip Service maintain strict anti-fashion values, subverting the mainstream while crafting high-quality clothing, though some brands have diffusion lines that toe the line of assimilation and other brands may not be as strictly anti-fashion in their practices as time shifts. Nonetheless, they continue to uphold these values as they struggle to survive the capitalist model.

Media Sensationalism and Its Impact

I’ve previously discussed the detrimental effects of goth’s sensationalism through the runway, goth’s growth from the underground to mainstream, and its commodification which all speak to media sensationalism. Now, I will be using this chapter to shortly discuss how gothic representation has been portrayed in media, made into a trend and transformed goths into products

A rebellion against the old system, the one we are born into and supposed to live by, so we rebel against it, in our appearance, our dress and our thoughts(Donnica 1:20). This is from a “Punks, Goths & Mods on Irish TV, 1983” interview, one of the earliest videos I could find. It gives us an accurate glimpse into the philosophies these subcultures were built on and the general public perception at the time. The interviewer continues by asking a series of questions to the previously mentioned punk, highlighting the stereotypes and general associations that the dominant hegemonic culture held about these subcultures. The questions cover topics such as his interest in violence, his acceptance by his family, his employment status, and his drug use.

As you can imagine most if not all of the answers contrasted his expectations. This is a clear example of how any act that went against the established norm was viewed as inherently wrong. It was typically unfairly associated with all the attitudes hegemonic culture held as unacceptable. This is cultural erasure. Perceptions of goths followed this timeline:

- 1980s: fear and ridicule, associations with death and satanism as religious conservatism were still strong and societal misunderstanding ran rampant.

- 1990s: curiosity grew as it began to expand into the mainstream, though still believed to be deviant.

- 2000s: widespread alienation and frustration amongst goths as their identity became commercialized and co-opted, leading to a loss of self.

- 2010s: cautious acceptance of goths as the sociopolitical landscape shifted and they gained broader mainstream recognition, though their subculture became diluted.

- 2020s: aesthetic popularity dominates as the misconception of goths becomes a sought-after identity, but feelings of resistance and disconnection amongst goths from commercialization are strong.

“Before the internet, interaction with the music and subculture were completely dependent on the physical space. This physical space included, concerts, specific goth “nights” at clubs, festivals, and other special events.” (Unger 8). Before the internet and therein social media the rate at which goth as a subculture was commodified could be tracked, as previously stated physical interaction was a necessity. So realistically when analyzing perceptions over goth’s 40+ year existence there is only before and after the internet.

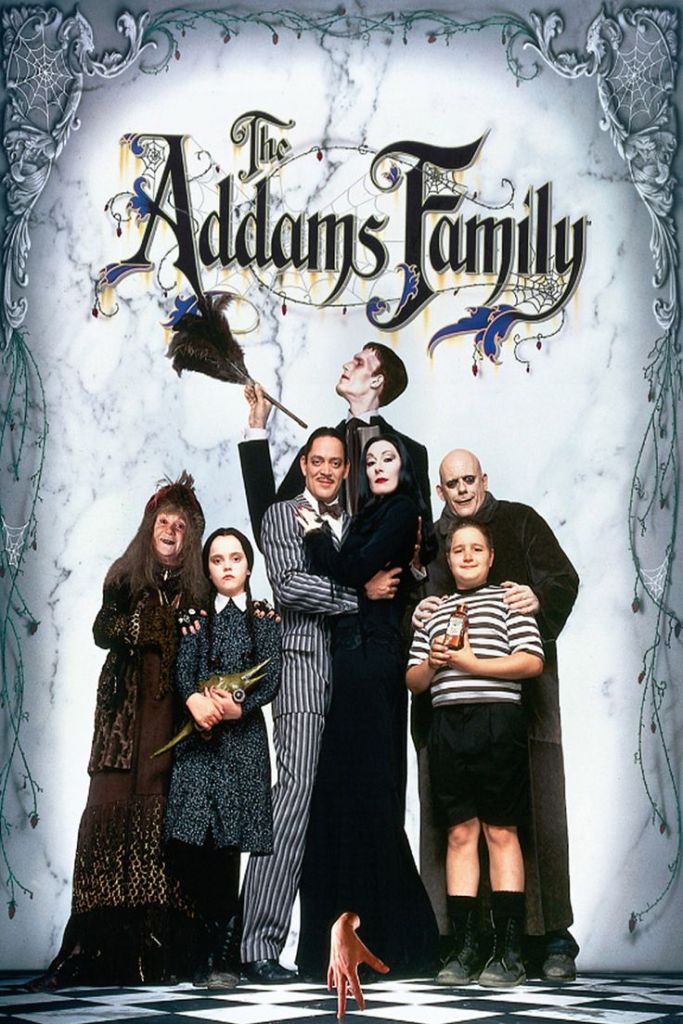

We have tackled before the internet where we could see the direct domino effect of this movement. Films like “The Crow” solidified goth aesthetics and attitudes, shifting public perceptions from fear and ridicule to intrigue and admiration. Likewise, The Addams Family and Buffy the Vampire Slayer helped normalize goth archetypes and a love of the supernatural. These portrayals, while introducing goth to a broader audience, often emphasized the aesthetic over the ideology, contributing to the mainstream’s fascination with goth as a spectacle rather than a subculture of resistance.

The last 15 years are critical in understanding the perpetual state of flux goth exists in and ultimately which side it skews to more. I would argue it skews more in favour of subcultural resistance. However, the power of social media as you know and will come to understand even further blurs the line. Tiktok, a good measure of the extent of social media’s impact and reach within 5 years accruing over a billion users, it has become the driving force of the fashion cycle and trends surpassing Instagram. As a result, this article will employ TikTok in its social media references.

In hindsight, it seems almost predictable that a music-based dancing app would concretely depict the present state of a subculture originating in music. “The striking outward expression of goth attracts outsiders to the aesthetic rather than the deeper implications of the culture.” (Unger 26). This highlights the way goth’s visual allure typically overshadows its deeper philosophical foundations, resulting in a superficial engagement with the subculture. Social media where visually striking content is prioritized over authentic narratives. The end goal of commodification is the creation of a consumable product and in this case that consumable product is goth.

“Instead of being goth solely for the love of the music, literature, or ideology, some measure their “gothness” by what products they can consume and claim ownership over.” (Unger 27). TikTok specifically capitalizes on this trend, thriving on its ability to sell identities through its “creators.” Within a capitalist framework, where people are both the product and the consumer, even goths despite their philosophy of nonconformity fall prey to the commercialization they fundamentally oppose.

After a thorough examination of commodification, media sensationalism, and the enduring values of the goth subculture, the result is clear: goth remains in a constant state of flux, balancing precariously between subcultural resistance and mainstream incorporation.

Ultimately, the visual appeal of misinterpreted gothic fashion will remain a public favourite, but its steadfast values of non-conformity, individualism, and creative expression prevent its assimilation.

This maintains my thesis. However, that constant flux leads to a perpetual state of the evolution of goth, cyber goth, romantic goth and haute goth to name a few. This state perceived to be a flaw is what allows the goth subculture to prevail. For every new trend derived from goth, there is an equal and greater subcultural resistance produced. In Goth’s bid to adopt what society rejects it has built an adaptability true to its ethos.

Works Cited

Bush, Leah. “An Overview of Goth as a Subculture of Consumption“. AMST498B: Fashion and Consumer Culture in America, 19 Dec. 2013.

Lady of the Manners. “Goth Fast Fashion, and Why It Isn’t Always a Good Thing.” Gothic Charm School, 16 Oct. 2021, https://gothic-charm-school.com/charm/?p=1602. Accessed 24 Jan. 2025.

Patton, Lain. “The Oxymoron of a Conservative Goth.” The Wooster Voice, 27 Sept. 2024, https://thewoostervoice.spaces.wooster.edu/2024/09/27/the-oxymoron-of-a-conservative-goth/. Accessed 24 Jan. 2025.

Newman, Sabrina. “The Evolution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture“. Johnson & Wales University, 26 Apr. 2018.

Tuzio, Vivienne. “Vivienne Westwood and the Rise of Punk and Anti-Fashion.” Fashion and Subcultures Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 2012, pp. 22-29.

Harriman, L. “Goth Fashion and Its Timeless Appeal.” Fashion History Journal, vol. 16, no. 3, 2020, pp. 74-80.

Marsella, Anthony J. “The Impact of Hegemonic Globalization on Cultural Diversity.” Global Studies Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, 2019, pp. 15-23.

Punks, Goths & Mods on Irish TV, 1983. CR’s Video Vaults, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDogh7J1-5s&t=158s.

Unger, Marlie. “Two Worlds and in Between: Becoming Goth in the Virtual Spaces of TikTok.” Bowling Green State University, Honors Projects Student Scholarship, Spring 2024.

Leave a comment